The novel coronavirus is disproportionately infecting Indigenous people in both cities and on reserves in Manitoba, which has emerged as a hot spot of the pandemic’s second wave.

COVID-19 cases have surpassed 10,000 in the province since the start of the pandemic in March, with First Nations making up 16 per cent of total infections despite representing just 10 per cent of the province’s population. At least 961 infections have occurred among members living off-reserve and 667 cases have been reported on-reserve in 35 communities, most of them in the fall.

Infections among First Nations members have tripled since the end of October, leading to 1,123 active cases as of Nov. 13 and 18 deaths since March, including seven in the past week.

Marcia Anderson from the Manitoba First Nations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Coordination Team called the acceleration of infections in the past couple of months “dramatic,” particularly the sharp rise in deaths in the past week alone.

“That’s incredibly concerning when we think about what we might experience in the weeks and months to come,” she said.

Dr. Anderson, a Cree-Anishinaabe public health doctor and vice-dean for Indigenous health at the University of Manitoba, said the province is seeing a consistent overrepresentation of First Nations people in infections, hospitalizations and intensive care units, which she says are “indicators of both higher rates of disease but also increased severity of disease.”

Indigenous people represent about 23 per cent of the province’s COVID-19 hospitalizations and 38 per cent of patients with the disease in ICUs.

Manitoba is in the grips of a punishing second wave that is overwhelming some of its hospitals and has led to the strictest lockdown in the country currently.

The province was one of the first to track the race of COVID-19 patients in an effort to detect inequities in the toll of the pandemic and it remains one of the few to do so. First Nations have been collecting that data to monitor how the virus is affecting residents living on and off reserve communities.

The Manitoba First Nations COVID-19 Pandemic Response Coordination Team is made up of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak, Keewatinohk Inniniw Minoayawin, and the First Nations Health and Social Secretariat of Manitoba.

Dr. Anderson told The Globe and Mail she expects the current trend will continue and they are working with partners to increase testing capacity and ensure people have supports to safely isolate at home or in “alternative isolation accommodations.”

She said data show that the health of First Nations people in urban environments is not better than than those in rural and remote locations.

“Urban First Nations people also have higher rates of inadequate or overcrowded housing than the general population,” she said.

The acceleration of infections on-reserve is happening elsewhere in the country as COVID-19 surges from British Columbia to Quebec.

According to data from Indigenous Services Canada, on-reserve cases have quadrupled since the end of August across Canada, with 2,253 total infections as of Nov. 12. Manitoba makes up more than 25 per cent of those cases, but the federal government’s tracking doesn’t include off-reserve population in urban locations such as Winnipeg, The Pas, Thompson and Brandon.

Manitoba First Nations, like many across the country, were spared during the pandemic’s first wave last spring. Leaders attribute that success to the quick mobilization and vigilance of First Nations to protect their borders, understanding the virus would inevitably come from outside their communities, and developing response plans for when that happens.

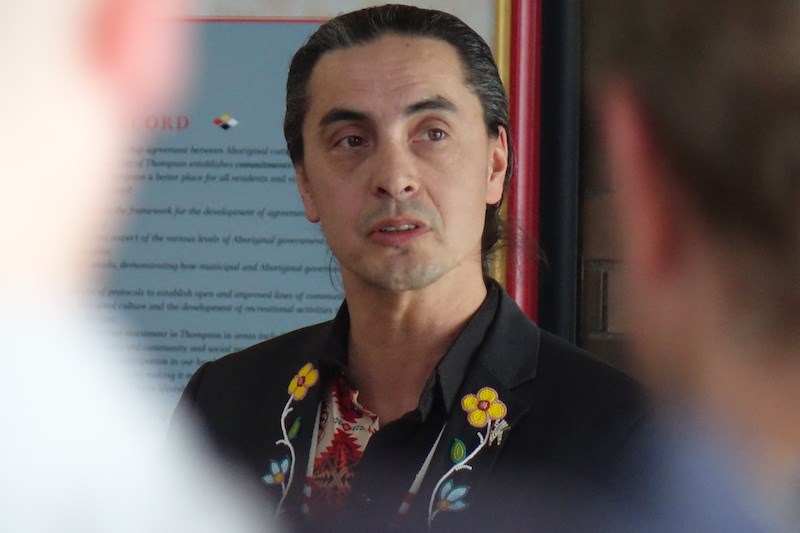

Grand Chief Arlen Dumas from the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs says the success from the first wave is also what “led to a little bit of apathy” and pandemic fatigue.

“These things where everybody kind of loosened up a little too quickly,” Chief Dumas told The Globe.

Onekanew Christian Sinclair, the chief of Opaskwayak Cree Nation, says the community implemented a number of measures, including a ”full lockdown,” after an outbreak last month that has led to more than 100 cases so far – about half of which are still active. It also resulted in the death of an elder resident in the community’s personal care home, where a second outbreak has infected all 28 residents and 13 staff. The first outbreak was linked to a wedding on Oct. 10 and a funeral on Oct. 24 in the community of 1,500.

Exposures at funerals in Cross Lake and Lake Manitoba First Nations have also been linked to outbreaks in the province’s northern region.

“We’re getting it under control in the sense of providing the resources and logistics that we need,” Chief Sinclair said.

A rapid response team will spend five days in the community to do rapid testing and contact tracing.

Indigenous Services Canada last week announced $61.4-million in immediate funding to support Manitoba First Nations and their pandemic response plans, following the “alarming rise” in cases.

In an interview with The Globe, Minister Marc Miller said the pandemic teams in the First Nations are key to ensuring effective responses are being carried out and that needs are identified by “people that have boots on the ground.”

April Sandberg is a member of Opaskwayak Cree Nation who lives in Winnipeg. Her family tested positive for the coronavirus in October after her husband first experienced symptoms. It wasn’t long before everyone in the north end Winnipeg household tested positive, including her husband, their children aged 1 and 4, and her husband’s uncle and cousin. She shared her experience of symptoms in a Facebook Live video after she recovered.

She says at her worst her lungs felt “full” and she had difficulty breathing. She “toughed it out" and is feeling better, but now worries about her extended family who lives in a small house in Opaskwayak, 630 kilometres north of the city. She told The Globe her brother is waiting for test results, which will affect everyone living in the overcrowded home, including her 19-year-old daughter who has asthma.

“It’s been pretty stressful just because I know how bad it gets and how quickly it spreads,” she said.

Opaskwayak Cree Nation is a major economic hub. Chief Sinclair said they’ve restricted most businesses and put up security checkpoints at main access points. The 60-room hotel has been turned into an isolation centre for community members.

The nearest hospital is in The Pas and the nearest ICU in Winnipeg.

“It’s really a high risk, volatile situation. We’ve got everybody all hands on deck,” he said.