An amateur astronomer from The Pas is part of a huge 13-year $200 million NASA project to study the aurora borealis across the Arctic, from Greenland to Alaska.

He is Delwin Shand, the caretaker of the THEMIS mission’s ground-based observatory (GBO) in The Pas which works 365 days a year.

“It’s a camera system,” Shand said. “The University of Calgary’s astronomy and astrophysics department, in junction with NASA, the Canadian Space Agency and the University of California at Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory are participating in a joint project. I look after their camera system and computer that controls it.”

Shand is the president of the Northern Lights Astronomy Club, which meets the first Thursday of every month at 7 p.m. at The Pas Regional Library. He is also the database administrator for the University College of the North’s support personnel’s record system in The Pas.

“Every night, once the sun sets in The Pas, this camera system starts taking a picture of the sky every three seconds until dawn,” Shand said.

The sun’s activity intensifies every 11 years, and 2013-14 was a peak time or solar maximum, when solar flares, coronal mass ejections and solar energetic particles coming out from the sun are at their highest frequencies. Auroras occur most frequently and are usually brightest during this solar maximum.

The amazing St. Patrick’s Day auroral displays were from a severe (G4 level) geomagnetic storm caused by two big explosions (coronal mass ejections) from the sun. It’s the most powerful storm since 2013, and was so intense it moved south towards the equator, and was seen as far south as Oregon and Illinois in the United States.

Shand said people know the auroras and the impact solar storms can have. A power outage in Quebec on March 13, 1989, left the entire province in darkness for over nine hours, because a substorm induced electric currents in power lines.

Shand said: “The power went out due to the power grid being overwhelmed through induction by highly charged particles … Energetic bursts of particles from the sun can damage and interrupt communication satellites and can make navigation impossible.”

Auroras are caused by solar wind, the continuous flow of electrically charged particles from the sun.

Shand said: “The northern lights have been observed by astronauts in the International Space Station during their orbits. There is a belt, or circle, that goes around the North Pole and it usually is out a little ways into the Northwest Territories and the Yukon.”

Severe substorms can be hazardous to astronauts orbiting Earth in the space station. Energetic electrons can charge the surfaces of spacecraft, damage electronics on spacecraft and rip through molecules in the living cells of unshielded astronauts.

Eric Donovan, a professor at the University of Calgary’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, is the principal investigator for the THEMIS cameras in Canada and a member of the University of Calgary’s Auroral Imaging Group. He is observing the aurora using ground and space-based digital imagers.

“It’s a NASA mission,” Donovan said. “The first camera went in, in Athabasca in 2004. The satellites were launched in 2007…By the time the satellites were launched, we had 19 GBOs deployed: the four in Alaska, and 15 in Canada.”

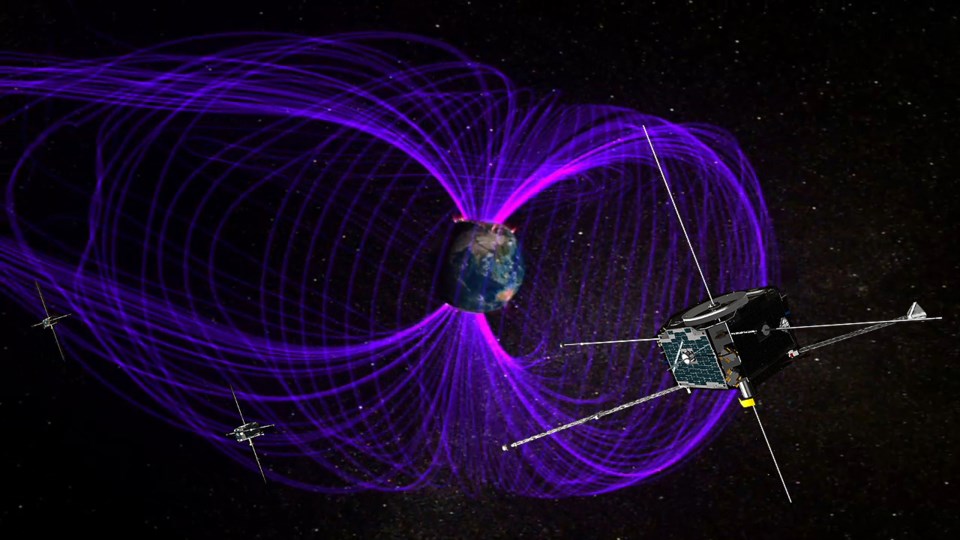

THEMIS started with five satellites which measure ions, electrons and electromagnetic radiation in space.

“Three are still called THEMIS, two are Artemis,” Donovan said. “They took the two outer satellites and moved them out into orbit around the moon a few years back.”

The University of California at Berkeley deployed the other GBOs in Alaska and Greenland, and there are now 17 in Canada.

“There are now 22 ground-based observatories: one in Greenland, 17 in Canada, and four in Alaska,” Donovan said.

Three of the 22 THEMIS ground-based observatories are in Manitoba in The Pas, Pinawa and Gillam. The GBOs take images of the aurora by shooting the night sky, and have magnetometers that record variations in the magnetic field at the Earth’s surface during auroral disturbances.

The GBOs open their shutters together for one second, every three seconds, to get a complete picture of the whole night’s sky.

Donovan said: “It’s GPS-timed. We turn them on at the same time across the whole array…We make movies every morning from last night’s data. We stitch together the mosaics to make movies.”

To see the movies, go to rtemp.ca.

The University of Calgary is responsible for all the GBOs in Canada, but the University of Alberta and Natural Resources Canada have their own magnetometers, which they are operating for some of THEMIS’s GBOs.

“The people who led this mission in the United States, NASA, launched it,” Donovan said. “The Canadian Space Agency and NASA funded the ground-based program.”

Magnetospheric substorms happen when the solar wind overloads our magnetosphere and causes the charged particles in its magnetic field linesto stream into the Earth’s atmosphere near the north and south magnetic poles.

These particles are protons and electrons, which collide with the atoms of oxygen, nitrogen and other molecules of gas in the atmosphere. The result is the luminescence of the atoms of the affected molecules. The electrons of their atoms are getting energized by the charged particles and causing the atoms to emit energy in the form of light.

“The solar wind puts energy into the magnetosphere all the time,” said Donovan. “It’s always blowing by, and buffeted by, the Earth’s magnetic field. There’s always magnetic reconnection on the day-side.”

He said the energy coming in from the solar wind is being dissipated through electric currents in the atmosphere, through the motions of giant clouds of charged particles in the magnetosphere, through the aurora and other ways. But two or three times a day there’s more energy coming in than can be dissipated, and the extra energy is released explosively in the form of a substorm.

We see the substorms as a sudden brightening and more dynamic appearance of the northern lights, or aurora borealis.

But he said a storm is a much bigger event and a fundamentally different process, because you’re pouring much larger amounts of energy into the magnetosphere.

THEMIS stands for Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms, and its primary objective is to identify the point of origin of the substorms within the Earth’s geomagnetic tail.

There are two competing theories for their origin. Donovan published a paper in 2008 supporting the theory that it expands outward, rather than inward, starting 50,000 kilometres from the Earth.

The THEMIS mission has made significant progress and is a top-ranking NASA mission.

Donovan said: “But it is also doing a lot of other things, very interesting and important science. It’s a very impressive mission. That data is used by hundreds of researchers around the world, to attack interesting science questions. The All-Sky imagers are a very scientifically productive project.”

THEMIS researchers want to discover, explore and understand our environment.

“That is what is driving the mission,” said Donovan. “What causes the substorm onset? How does the radiations belt work? These kinds of questions. The knowledge gained leads to all kinds of practical applications.”

Donovan’s group is doing research with people who do GPS work, and with those who do space weather research with THEMIS’s all-sky images.

He said this is fundamental research that is really benefiting Canada, which plays a big role in the mission.

“The THEMIS mission cost $200 million,” said Donovan. “Canada has spent maybe $4 million on this, over 12 or 13 years. So we get a really good, big, international role in stuff, for a fairly inexpensive investment. We are getting a big bang for that buck on the international stage, in the international scientific community.”

He said the THEMIS mission will go on for another four or five years, and they are now developing new observing systems.

“We are bringing on different additional observations on the ground, such as radio receivers and different kinds of cameras,” Donovan said.

He said another mission called Magnetospheric Multi Scale (MMS) was just launched.

The United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket with NASA’s MMS spacecraft onboard was launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida on March 12, and NASA has already begun commissioning and testing all their instruments in space. Their observations of magnetic reconnection will begin in September and the mission will unfold over the next few years.

“It’s a $1 billion mission,” Donovan said. “It’s a NASA mission. I believe we will have a significant role in that project, because of these cameras.”